Thursday, May 12, 2016

Un-civilization - Butchering a Gemsbok in the Kalahari Desert with the Gikwe Bushpeople

"Next the two men removed the rumen, the first stomach of ruminant animals, where the grass they bolt hurriedly is kept in quantities to be coughed up and chewed thoroughly when the animal is lying in the shade. Ukwane lifted the rumen out carefully, like a great water sack that might burst suddenly, and hurried with it to the pit lined with the skin. There he slit it and water gushed out, every drop saved by the skin. Ukwane and Gai removed handfuls of its contents, a yellow, pulpy mass of partially digested grass, and they squeezed each handful dry into bowls, tsama-melon rinds, and ostrich egg water containers that the women had brought forward. They did not mind two great white worms that were discovered living in the rumen, for as soon as enough water was collected, the people all had a long, satisfying drink. Some was pressed on me by Tsetchwe; I could not bring myself to drink it, but I did taste it and found that it was not too unpleasant, although it tasted strongly as intestines smell. It was fresh, however, it was only the liquid from grass, and I thought that if I had no other water I too could drink the water of rumen."

From Elizabeth Marshall Thomas' The Harmless People about the ways of the Gikwe hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari who have no access to water for eight months out of the year.

Monday, May 9, 2016

Civilization

How do we become un-imprisoned without rejecting a civilization that is all we know?

By turning the purpose of civilization around so that it gives back to nature rather than just taking everything (without so much as a thank you!) Or at least attempts to gives something back, conscious of the need for balance, and that the long term survival of ourselves - our own self-interest - require a more balanced way of living.

By turning all of the powerful capabilities of civilization away from ruthlessly exploiting all other life on this planet towards nurturing life and building habitats not just for ourselves but also for the incredible wealth of life that we are so fortunate to live together with and upon which we depend. By coming to see ourselves truly and accurately - scientifically - as the primates that we are, primates in a living landscape, and not as the gods or children of gods that our religious traditions imply (valuable culturally and morally as these traditions are,) and in that seeing, coming to know that we can’t just keep on taking without contributing to the landscape in which we live.

We can’t so much reject civilization but work to re-direct it, to clarify the purpose of civilization, such that we may again be its participants, rather than its victims, as so many of us seem to be, even the most economically successful or celebrated.

There is a a sacrifice to be made, a giving up, because that is necessary. We can’t have it all, if we are to live honestly. What we must give up: the sense of entitlement to infinite supplies of food, shelter, transportation, health-care, entertainment, security, and even information that is so common in the First World. Mostly, what needs to be sacrificed are delusions - comfortable delusions, delusions of comfort - which are being ripped away anyway.

And in exchange for sacrificing these delusions, we might have a shot not just at a more accurate understanding of ourselves but also a more reasonable way of living. A way of life with a future to it, and not that Blade Runner future.

This is not to say that by sacrificing our delusions that we will be assured of a viable future. This is not about bargaining with the destiny our current civilization has us set up to meet. There is nothing sure or certain in this world. It is simply to say that there will be sacrifices to be made. The future is not cornucopian. There are real limits which can’t be wished away. But there are paths that are more viable than others, attitudes that are more or less constructive, perspective that are more or less useful.

Being a “doomer” is not particularly useful. But trying to see ourselves and our predicament clearly and having a framework by which to act upon that clarity of vision is useful, a framework which is bigger than the common humanism/anthropocentrism, such that we act in ways that benefit not just our own species but other life-forms as well. Also, useful is a framework that does not reject the countless generations worth of work that has gone into building the civilization that we more or less comfortably inhabit, but instead turns our best capabilities toward better goals and the profit, the excess that we generate back to where it belongs, the larger system of life.

Saturday, May 7, 2016

The New Question

What can we, as a species (or a nation or a state or town or a business or an individual), contribute to the community of life?

It's always been about what can we take, more efficiently than anyone else. It's always been about EROI (Energy Return on Investment), and how much extra we can suck out of the system by all our cleverness, bunch of monkey grifters that we are.

Maybe it's time to have a little pride and think about giving back. About making something that's good for everybody: microbes, rodents, coral reefs, elephants, and all everything in between. Imagine what that might be like, just to think that way, and then start living the question.

Of course there are many wonderful people who already are living the question, such as my friend Megan Lamson, who has been leading coastal beach-cleanups for years. Cleaning up after ourselves is one step in growing up and towards giving something back to the community of life.

It's always been about what can we take, more efficiently than anyone else. It's always been about EROI (Energy Return on Investment), and how much extra we can suck out of the system by all our cleverness, bunch of monkey grifters that we are.

Maybe it's time to have a little pride and think about giving back. About making something that's good for everybody: microbes, rodents, coral reefs, elephants, and all everything in between. Imagine what that might be like, just to think that way, and then start living the question.

Of course there are many wonderful people who already are living the question, such as my friend Megan Lamson, who has been leading coastal beach-cleanups for years. Cleaning up after ourselves is one step in growing up and towards giving something back to the community of life.

Friday, May 6, 2016

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

One of the greatest barriers we have to understanding other life-forms is the burden of misinformation we carry in our heads. - Elizabeth Marshall Thomas in The Hidden Life of Deer.

I don't know what I'm doing, but if there's one thing that I consider my job, my calling, the thing I'm supposed to do, it's trying to understand other life-forms. That's why I'm a rancher, that's why I'm in agriculture, because I get to spend my days around other life-forms, and also because I don't think you can understand other life-forms without understanding how we are bound to each other in life and death, in feeding and in eating. It's not enough to have some academic or intellectual or scientific or otherwise symbolic knowledge about the ways we are bound together as bodies, as matter. It's necessary to be entangled and impure, in the middle of the struggle for survival, as close as possible to the transactions that keep us alive and to know, to see what that costs. Otherwise it's too easy to forget and not see, to live in our entirely human world.

Here's another great writer to whom we will all be indebted if we are so lucky as to negotiate a way out of dystopian ruination that we seem to be headed towards so inexorably - the anthropologist-ethologist-novelist Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

I don't know what I'm doing, but if there's one thing that I consider my job, my calling, the thing I'm supposed to do, it's trying to understand other life-forms. That's why I'm a rancher, that's why I'm in agriculture, because I get to spend my days around other life-forms, and also because I don't think you can understand other life-forms without understanding how we are bound to each other in life and death, in feeding and in eating. It's not enough to have some academic or intellectual or scientific or otherwise symbolic knowledge about the ways we are bound together as bodies, as matter. It's necessary to be entangled and impure, in the middle of the struggle for survival, as close as possible to the transactions that keep us alive and to know, to see what that costs. Otherwise it's too easy to forget and not see, to live in our entirely human world.

Here's another great writer to whom we will all be indebted if we are so lucky as to negotiate a way out of dystopian ruination that we seem to be headed towards so inexorably - the anthropologist-ethologist-novelist Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Entertainment

Every so often I like to pick up books at semi-random off the new books shelf in the library. One of the serendipitous discoveries this round is a reprint of D.H. Lawrence’s Mornings in Mexico (1934), a collection of essays from his time in Mexico and the Southwest of the US.

I’ve never been able to get very far into Lawrence’s famous novels, but I’ve loved his wild, hypnotic poetry since I was a teen. I think you could accuse Lawrence of various kinds of intellectual sins; his writing is both baroque and brutal: opinionated, patronizing, flat-out ridiculous half the time, but the rest of the time he’s more right than any careful, thoughtful, tactful writer could ever be. So it is with the thinking of poets I suppose: for the most part indefensible but occasionally crucial.

His most striking essay in the collection is “Indians and Entertainment” in which he compares the metaphysics of Western drama with the anti-metaphysics of Indian communal ceremonies.

Lawrence says of the Western tradition of entertainment from classical Greek drama to Hollywood: “The secret of it all, is that we detach ourselves from the painful and always solid trammels of actual existence, and become creatures of memory and of spirit-like consciousness. We are the gods and there’s the machine, down below us.” From drama we’ve progressed to the cinema and modern man’s passion for movies: “In the moving pictures he has detached himself even further from the solid stuff of earth. There, the people are truly shadows; the shadow-pictures are thinkings of his mind. They live in the rapid and kaleidoscopic realm of the abstract. And the individual watching the shadow-spectacle sits a very god, in an orgy of abstraction, actually dissolved into delighted, watchful spirit.”

We have many vices in the West. Some of our vices are ruthlessly destructive. This vice, this addiction - our lust for entertainment - is the one that may well be self-destructive. It is slowly luring us into an abstracted, distracted passivity.

Of the Native American/Indian idea of entertainment, Lawrence says, “ He hasn’t got one.”

He says that the consciousness of the Indian and the West are irreconcilable, fatal to each other: “That is, the life of the Indian, his stream of conscious being, is just death to the white man. And we can understand the consciousness of the Indian only in terms of the death of our consciousness.” By this dichotomy, Lawrence tries to show up the dishonesty of well-meaning, enlightened Westerners who consume Indian communal performances as entertainment and spectacle.

“The Indians dance around the drum, singing” Theirs is not an entertainment but an experience, a renewal, repetitive, wordless, meaning nothing but joining everything together, no beginning and no end.

“Yet perhaps it is the most stirring sight in the world, in the dark, near the fire, with the drums going, the pine-trees standing still, the everlasting darkness, and the strange lifting and dropping, surging, crowing, gurgling, aah-h-hing! of the male voices.”

The Indian ceremonial is a direct experience of the wonder of the world, in the deep places “of the blood” and shared life.

Lawrence says a great deal more about the Indian ceremonies and dances and a modern anthropologist would shudder at most of what he has to say. He shamelessly projects his own artistic obsessions onto Indian ceremonials.

And yet, there is the door he cracks open for us, we entertainment-besotted global consumers tethered to our smartphones, our Netflix and HBO.

We could experience the world again, instead of succumbing to our entertainment. If we experienced it, perhaps we would love it with the intensity we need to summon to nurture life as a conscious goal. This would be a startling innovation within our civilization, which has always more or less taken life for granted.

To experience the world costs nothing, but we may have to die to everything we think we know about the world to walk away from entertainment. Perhaps it is more dangerous than we can possibly imagine. The abstractions in which we are enthralled, perhaps they protect us from the harsh realities of our own voracious human nature. We may have gone way past the possibility of experience as a chosen thing, and must make do with the virtual delights of civilized entertainment because there are simply too many of us humans. Without the resource extraction efficiencies of the global economic machine we would not be able to keep ourselves fed, and without the entertainment complex we would see all too clearly our growing imprisonment in our own economic machine. That may be the cold, hard truth of the next few decades, but I'll not stop acting as if we can choose otherwise.

Friday, April 29, 2016

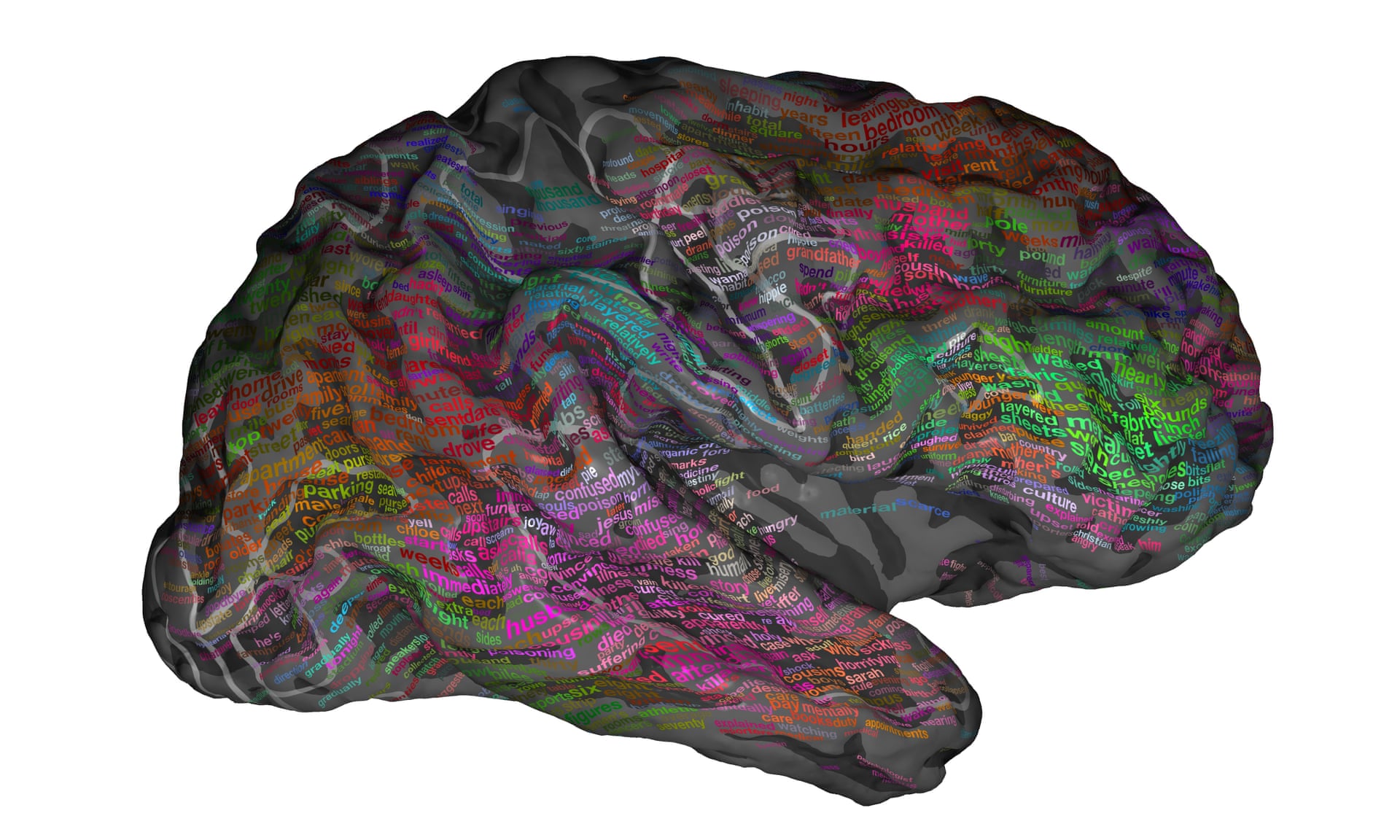

What is a brain?

"Scientists" have built a map of how words activate the brain. (I wish we would stop doing that, conferring the mantle of the All-Powerful Oz that goes with the word "scientist" upon what amounts to some guys and girls who happen to have a certain kind of eduction and access to some fancy equipment; I'm imagining the headline "Literary Critics discover how words are organized" or "Ranchers build multispecies biomimetic symbiotic system") This was done by putting some people in an MRI scan and reading stories to them. So, it was a bit of a literary enterprise. I wonder when, if ever, we will come to see our minds as bigger than our brains. Or care that our brains are not only lit up by words and numbers but by our natural environment as well, and that those connections are more important to the brain, to the entire organism, than our relatively recently acquired verbal and symbolic skills.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/apr/27/brain-atlas-showing-how-words-are-organised-neuroscience

|

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/apr/27/brain-atlas-showing-how-words-are-organised-neuroscience

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Hominid

I've been reading:

which has been helping me with the aforementioned project of stripping away some of the human obsessions and seeing us for the hominid/primate animal that we are. Tattersall, in fact, makes the point that the theoretical framework of the field of paleoanthropology (finding and interpreting hominid fossils) has been seriously skewed by a persistent insistence on seeing ourselves as the crowning glory of all creation (he calls it human exceptionalism), such that all hominid fossils lead to us, when in fact the fossil record may indicate a more complex family tree, in which we had cousins and distant hominid relatives. Who might be around now but we pretty much ate them. Okay, out-competed them, part of which might have involved eating them. That explains a lot about us, about how we're so damn afraid of ourselves, and have a passion for depictions of hominid on hominid violence. If you're a geek like me, Ian Tattersall's books, of which there are many, are a great read. Especially after feminist quantum physics. You'll not think about being human the same again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)