I was a troubled teen. “Reality,” by which I mean the social reality of the US in the late 70’s and 80’s, didn’t feel right. It seemed to be missing something, some depth of feeling or significance. There was a flatness to the social world, an ir-reality, a woundedness, as if something had been amputated. When I was very little I experienced this as an actual spatial distortion and disequilibrium. As I got older this changed into an emotional distance, an enduring alienation. I think this is a common experience. As the years passed this got “better,” I got along, by which I mean that I probably internalized the tension of alienation, like everyone else.

And yet I did not get along. I could not commit to either “reality” or to some kind of “alternative,” artistic escape into the world of fiction, representation, aestheticism. Neither felt real or whole or honest. Eventually my search for a way of life that ‘felt right’ led me to join my family in the project of building a cattle ranch from scratch. I discovered, in this endeavor, a life that satisfied my yearnings for engagement.

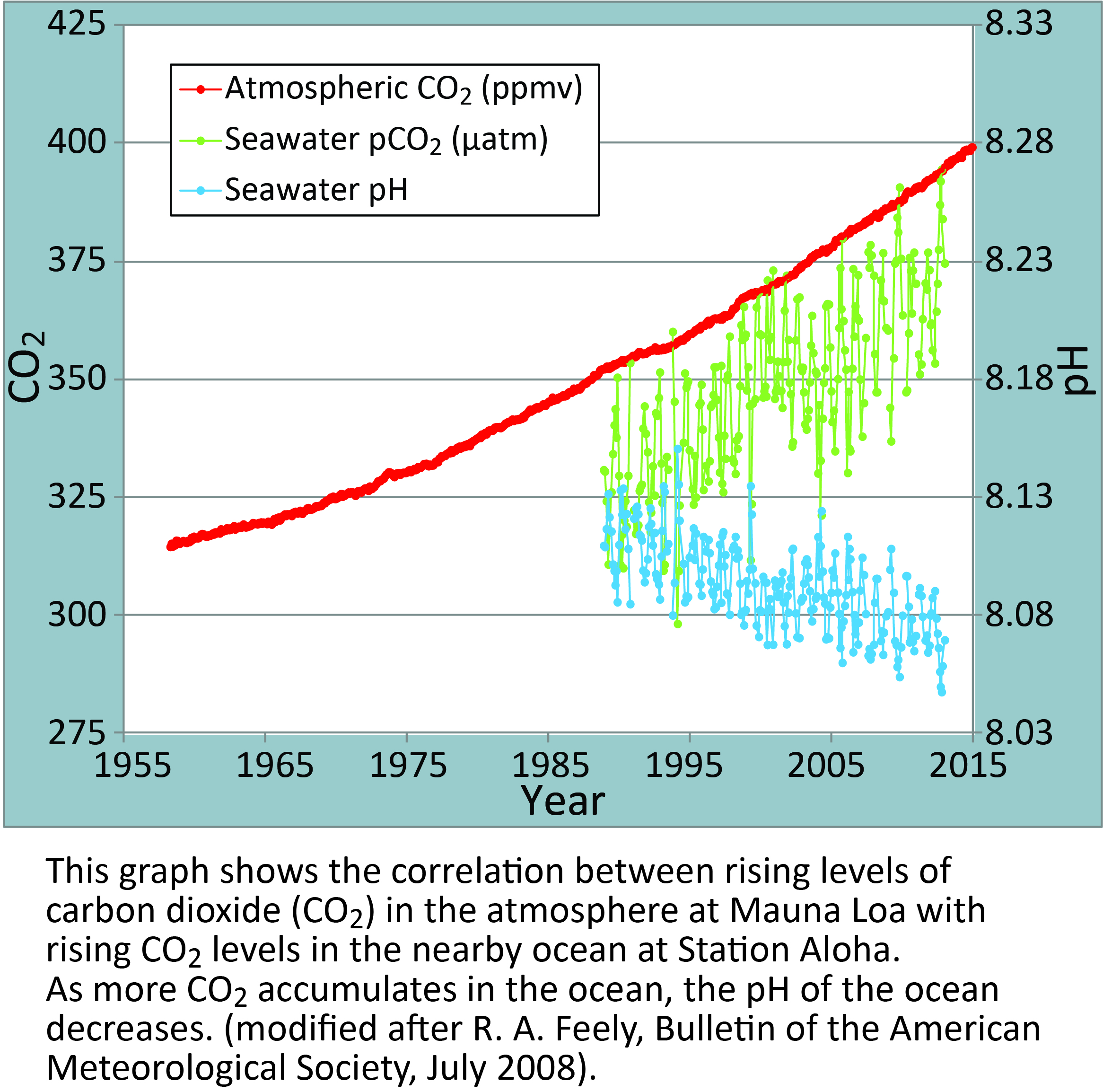

Still, I want to understand where that alienation came from, what it meant and to articulate what the missing dimension is that makes the difference between a flattened existence and a deeply felt life. The process of being educated, of joining the world of adults is one of gradually increasing pressure to conform, compete, succeed and fight for dominance. Jobs, money, economic security, social prestige. That is what we learn to focus on. That is what we spend our strength and time on accumulating. But this social/economic realm is only a very small cut-out portion of what actually exists in the world, a small circle into which we have mentally corralled ourselves. We have gradually cut almost everything our of our consciousness but what might be considered part of the economic machinery of civilization

I’ve come to believe that what assuages alienation is quite a simple thing — a slight change in what one focuses on and values - a refocusing that brings back into the picture what we cut out from it. A change at the level of what, in the old days, used to be called soul, thereby to indicate something that was both immaterial and deeply tied to the body, to material particularity.

To be clear, the “soul” I am interested in is not the Christian soul, it is the older concept that has ties to the sea and the wind in the trees. To be further clear, I don’t think that one “has” a soul, or “is” a soul. I am interested in “the soul” as a disruption - a question mark in the shape of the evening sky or the morning light, of mountains or waving grasses. “The soul” is Pandora’s box, where we buried it all - all of the impediments to “reason” and “law,” everything that was inefficient, wayward, and un-scientific. “The soul” is the whole of our human story, from Zhou dynasty dragon bones to Victorian steam engines to Brazilian favelas, from Rumi to Las Meninas to The Matrix. And it is all that we cut out of our human story in our impatience for some kind of glory. “The soul” is also a reminder of mortality and extinction, of the intimacy with all other life that our death enforces. A thought, a word, a possibility, only, which, if it does not help us see more clearly, is worthless.

“The soul” is a word that has been shaped by Christianity for so long that it is difficult to disentangle it from its history. One thinks immediately of disembodied, immortal spirits, of God, of Heaven, of churches and religious ceremonies. That history is essential, but it is also distracting if one would re-think the basis of what we now call, in our flattened way, consciousness. “Anima” is a word with far less baggage and with its close kinship to “animal” is less coded for anthropocentrism. But the word is not so important. What is important is the displacement of the psychic barrier we have constructed between “our” consciousness and everything else, the platform that we made to separate our “selves” from everything else. What is important is that we let go of the self-imposed delusion that we are distinct, separate, and superior to all other matter in the universe.

By reserving the realm of spirit/mind/soul exclusively for ourselves and defining all else as dumb matter, we cut ourselves off from the actual reality that we come from somewhere and depend upon an environment that has as much claim to life and mind as we do. Our mistake in the West is that we defined this quality of soul/spirit/mind exclusively in terms of the human, in our image as it were, and as our exceptional privilege and endowment. In that move, which is so closely tied to the doctrinal developments of the monotheisms (which then influenced our particular culture of science), we stepped into a delusion, which may have been useful, powerful even, for a time, but is, ultimately - like any delusion - maladaptive. What is more, in denying mind to all other creatures we came eventually to denying its existence even to ourselves, and to the despair and flattened existence that characterizes our late modern culture.

Unfortunately this mistake is ancient and is entangled with so much of what we consider normal that it is difficult to distinguish and correct the many paths of this delusion through our shared sense of reality. But if we would be healthy again, if we are to have a techne of life, a reinvigoration of our relation to life, rather than an ever-increasing psychic reliance on the technology of machines composed of “dead” matter, then the difficulties are worth encountering, I believe.

What does it mean to make this shift in focus? How does one track the implications of our mistakes in overvaluing our human-ness - in our excessive humanism? What are the challenges one might face in making this change in perspective? Will this more accurate foundation provide the possibility of a less frantic civilization? Ultimately, how does one live, in practical terms, because that is the true measure, how does one live?

Some might think that to let go of this delusion is suicidal and irresponsible, that it will mean that we relinquish our will to excel as a species. That it will cause loss of control and therefore suffering and death. It should be clear that this is the psychology of a messed-up adolescent, whose distorted, fragile identity must be defended by threats of suicide. Perhaps, it is time to take up the responsibilities of adulthood, with its burdens and its rewards. Adulthood is a sadder, more humble state, it is true, but less destructive, self-centered, and frustrated. Adulthood is also the time of making, of nurturing and giving, of a wider viewpoint and more varied pleasures.

By thinking of ourselves as separate and superior we have put ourselves into a very small box. We have limited our joys and pleasures - what “counts” as joys and pleasures - to a very short list: adornments, toys, food, houses, more toys, entertainment, vacations. We have limited what “counts” as knowledge to that which is produced by a very small set of procedures and attitudes which we call science. We have limited what “counts” to what can be quantified in some form or another. We have the quantities but lost everything else. We have facts (scientific) but we find them difficult to understand, and we have intricate things (technology) but don’t have any framework to put them to a use greater than the most superficial amusement or the most atavistic destructiveness.

In our Western tradition, the philosophy on which we have built our science is itself based on medieval politics/religion (one God, one king, one president, one true science). “Truth” or the true meaning of facts descends within that power structure. It is a structure that is, of course, out-dated but still operational. We replaced the warrior-God with a science-God, but it is still one separate, superior God and ruler that is the source of authority and truth.

We missed something important in our intellectual development. And we had our reasons for doing so quite deliberately. We wanted to set ourselves free from death (what more emotionally compelling reason is there?) and our dependence on Nature (also an appealing idea on the surface.) Childish fantasies, of course, but how were we to know that when our God himself seemed to endorse such ambitions?

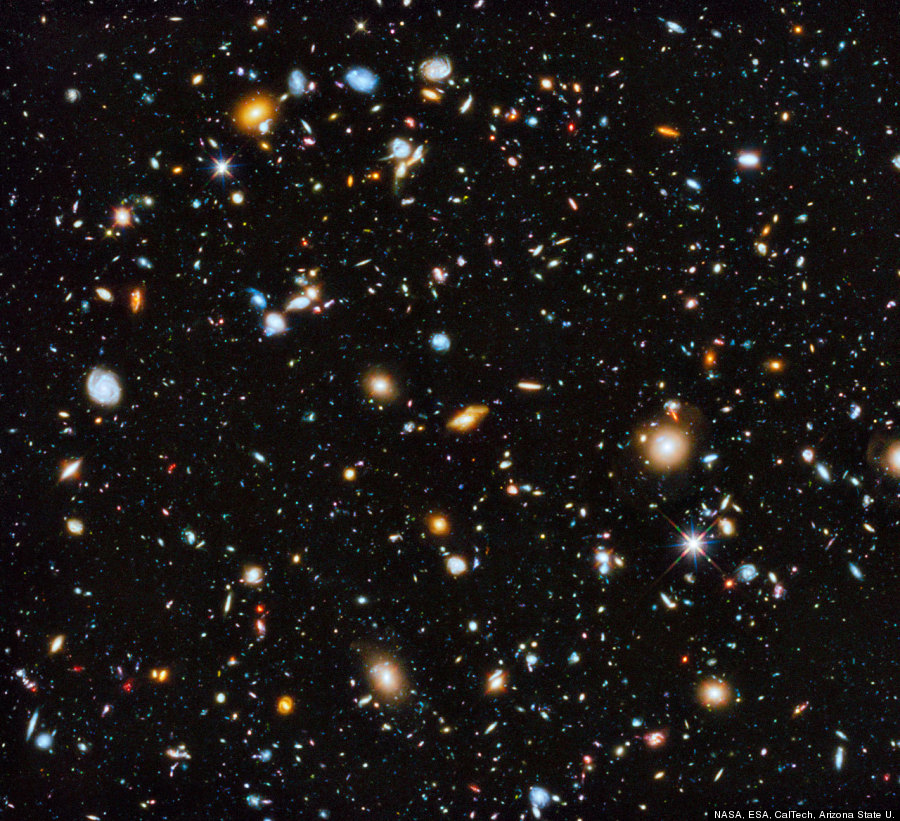

The perennial mind/body problem should have been a warning that we missed something important in the foundation. That we have a block there; that there are unresolved issues. Perhaps it is simple enough to resolve them. Let us say that matter is mind, mind is matter. Which doesn’t mean that one can dissect the brain to find “consciousness” because “consciousness” is not just in the brain. At the risk of sounding retarded: x=x , x being “consciousness” and x being the Universe. I know, it’s so simple it’s stupid, but we missed it all the same and we’ve been floundering about ever since, chasing childish fantasies of power and glory and deathlessness. I am speaking of civilization here, of course: our Western civilization, taken as a whole. (We’re terrified of this idea, of x=x, because it means we’re nothing special, and therefore don’t have a special license and dispensation to be masters of everything.) There have been and are instances of practice and thought on more solid foundations (and also therefore less spectacular, brilliant, neurotic, destructive, dominant.)

What does it mean then if x=x, if mind equals matter and matter equals mind? Does it change how we educate ourselves? How we get our food, shelter - fragile, contingent creatures that we are? How to talk ourselves ( and each other) down from the tendency to delude ourselves - to ignore reality - in our lust for short-term dominance? How do we grow out of that (warrior) hero obsession that we have, which set loose in the world makes life so difficult for everybody.

Yesterday I went for a walk in the evening. Rain tinted pink by the sunset was falling onto the violet sea in the distance and the horses were grazing in lush grass. Their way is so simple. They are up to their knees in food, most of the time. They don’t have much “ambition.” They have beauty and the capacity for mobility in their own bodies.

If we thought that x=x, perhaps we could lighten up on this immense project to make x not equal x, this immense effort - what amounts to a military operation by civilization - to maintain the inequality in our favor, to maintain this essential distinction between our selves as “higher consciousness” and everything else, To make and get marginal returns off of that inequality, which we insist is our birthright as a civilization. On which birthright we’ve constructed our elaborate, highly leveraged lifestyles. And we’re amazing, with our culture and civilization and all its toys. But not more amazing than anything else that gets along with x=x.

Maybe what x=x might mean is not another thing to talk about or do something about, but simply to let that possibility be, maybe that’s enough for now. Maybe x=x means that we can stop making things mean other things. Perhaps it is exactly the first step in un-meaning: in a process of un-peeling the layers of meaning that have accreted onto everything and that makes us confused and crazy. I really don’t know at this point.